“In 1828,” reads the text that opens The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser (or, to translate its original German title, Every Man For Himself And God Against All), “a ragged boy was found abandoned in the town of N.”

The ‘N.’ is Nuremburg, but the faux-reluctance to identify the location of this real-life mystery hints early at the film’s novelistic approach to historical materials. Indeed, Werner Herzog is barely interested in the enigmatic origins of a foundling who had apparently been deprived of all human contact before his sudden emergence (knowing just one phrase of German) as a teenager. Instead, typically, Herzog is more preoccupied with anthropological issues, casting his pre-cultural everyman into a world of social pretence, academic pomposity and dehumanising exploitation, and seeing what comes out of the ensuing confrontations.

Always closer to the children and animals that he encounters than to the adults, Hauser is both wide-eyed innocent and holy fool, exposing the unnatural follies of those around him while embodying Herzog’s frankly barmy thesis that it is civilisation which ruins humanity.

“It seems to me that my coming into this world was a terribly hard fall,” declares Hauser after he has been taught to speak – and like his childlike protagonist, Herzog himself struggles to find his feet, at first meandering about in dull period detail, and only beginning to come into his own at the point, about a third of the way in, where Hauser joins the local circus. From here on in, with its dwarves and camels, its freaks and wild outsiders, The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser at times comes across as a summation, even a pastiche, of Herzog’s entire early-Seventies filmography – but at least in this parade of caricatured grotesques who amplify and reflect Hauser’s alienation and exasperation (“I am so far away from everything”), there is something at last to hold the attention.

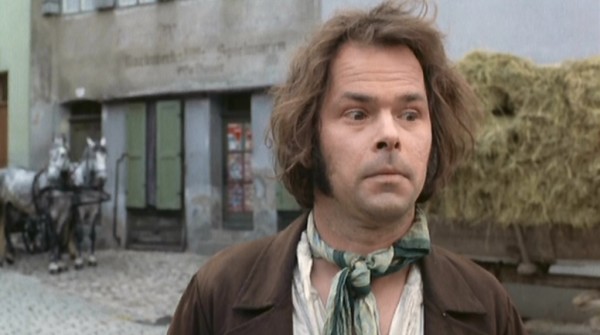

Herzog’s real masterstroke is the casting of troubled Berlin street musician Bruno S. A natural fit for the visionary lost boy, he would later rejoin Herzog for the thematically similar – but better – Stroszek (1977).

Anton has awarded The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser three Torches of Truth