Have you ever had a dream that was so alike your real life? So mundane, so nothing-y, so run-of-the-mill that when you wake up you’re unsure if it was a dream, or if it was in fact reality? Michel Gondry’s understated ‘The Science of Sleep’ showcases the true capacity of his creative visual flair in the tale of a young man struggling to make sense of his life and his dreams and how, on occasion, the two can blur and form something really quite extraordinary.

Gondry is perhaps best known for his 2004 Academy award-winning ‘Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’ in which he was noted for his inventive use of both reconstructing and deconstructing the film’s mise-en-scene – enabling him to create something both visually stunning and completely surrealist. The techniques he employed within ‘Eternal Sunshine’ are at their finest, at their most sensational and at their most captivating in ‘The Science of Sleep.’ As soon as the opening credit sequence begins, there is a sense of both haunting nostalgia and incredible creativity in every visual that is on screen: from viewing the inside of the central character’s mind (in the form of a cardboard box), to ‘baking’ a dream in the same way one would a cake, everything is beautifully ‘other-worldy’.

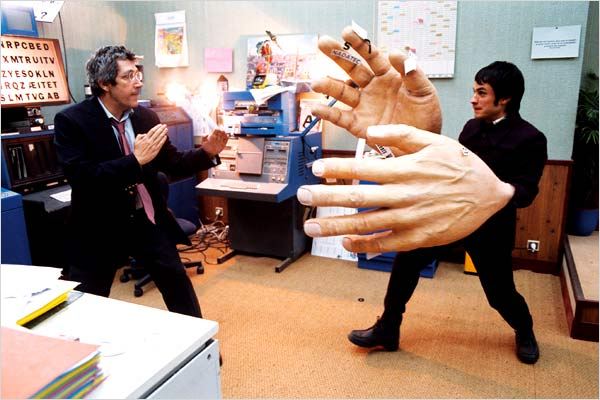

There is something in the characterisation of the film’s protagonist Stephane (played by the fantastic Gael Garcia Bernal) that is relatable and incredibly likeable. The normality and humdrum routine of his new job working in an office is often radicalised by his fanciful daydreams that play out like something from the pages of Lewis Carroll.

What makes the film so interesting, is that the more Stephane sleeps and daydreams, the more his dreams become intertwined with his reality. There is a wonderful scene in which he dreams he writes his neighbour a letter and posts her it, only to then awaken in his bathtub, with wet foot prints leading out of his apartment. The more confused and clouded his reality and dreams become, they are as equally confusing for an audience to make sense of too. The film plays like one big dream sequence. It is utterly mesmerising.

I find it incredibly rare for a film to offer both style and substance in equally fantastic measure without one trying to over-tip the other. Stylistically, Gondry is masterful and offers a platform for audiences to use their own imagination; to be a part of the film. The purposely flimsy set pieces and the often hand-drawn scenery is both fantastic to look at and also serves as a means to be a part of this fantasy world. It’s as much in our imagination as it is in Stephane’s. In terms of substance, Gondry has created a wonderfully original tale of seeing the wonders in life in something of a childlike manner. For 90 minutes, the pressures and responsibilities that come with adulthood are lifted and a wonderful world of creativity and escape is before us.