Last Friday marked the release of one of the most anticipated films ever made…The Dark Knight Rises (2012) . It’s been seven years since Christopher Nolan brought Batman back from the clutches of camp and redefined the Dark Knight for a whole generation as a truly modern cinematic icon. However, looking at the representations of character on screen through the past, and in particular, Nolan’s modern and edgy take, illustrates just how flexible the character is, from camp humour, to pop-gothic, and then all the way to gritty reality. No other superhero can be viewed through such a fragmented prism, able to embody so many different ideals, and yet endure with such a distinctive identity.

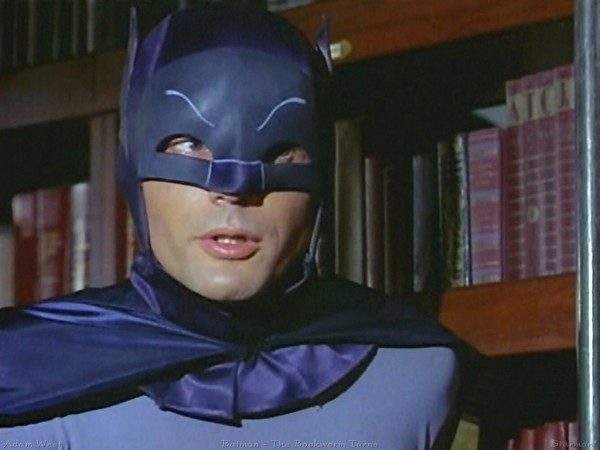

Looking back at 1966′s Batman: The Movie, with Adam West kitted out in Spandex, with bizarre eyebrow features on the cowl, a smile beaming across his jolly face, you would hardly believe Batman began life as a dark avenger of the night. The kitsch and camp nature of this particular interpretation is legendary, and would make Batman hugely popular across the world. However, it also did more harm than good to the image of the character, as colourful sets, insane gadgets and ridiculous puns would become synonymous with him for decades.

It would take another 23 years before Batman would return to the big screen as a young Tim Burton, inspired by Frank Miller and Alan Moore’s dark graphic novels of the 1980s, brought the complexity back. With Michael Keaton playing a brooding Batman and an eccentric Bruce Wayne, Burton was able to create a twisted world, much like that seen in the original Detective Comics of the 1930′s, in perfect harmony with his hero. It is still a striking vision, with his Batman stoic, but slightly cold and inaccessible. However, Batman Returns (1992) was more problematic. Unlike the 1930s comic book come to life of Batman (1989), Batman Returns is most definitely a “Tim Burton” film, not a “Batman” film. With giant duck boats and rocket launching penguins, Burton’s distinctive brand of pop-gothic excess overwhelms the film, as the grotesque and the larger-than-life ultimately create a more confused film in which Batman almost becomes part of the scenery.

While Tim Burton must take some of the blame for the eventual capitulation of the franchise due to his excesses in tone and style, Joel Schumacher’s neon tinted descent into pure camp and total spectacle was always going to divide audiences. Both Batman Forever (1995) and Batman and Robin (1997) suffer from foregrounding eccentric villains and young heroic sidekicks; keeping Bruce Wayne/ Batman as a shadow rather than an a dominant force, his torment almost completely absent in Batman and Robin, as angst and jealousy turn the dynamic duo’s relationship into one big lover’s tiff. However, despite critical derision and fanboy disappointment, both films still proved to be box-office smashes.

In retrospect, it is arguable that in his unashamed devotion to spectacle over all other elements of filmmaking, Schumacher’s take on the character understands the power of Batman as a pure icon, creating the first post-modern Batman on film; although at the cost of his character’s defining darker traits and motivation.

The reason Christopher Nolan’s Batman resonates so deeply with audiences is because, above all other cinematic interpretations, it strips the character down to his essence and places him firmly in the context of the world we live in today. A time of uncertainty and fear, where we are more connected and yet more globally dislocated than anytime in our history, and the threat of terror, from outside and within, is ever present. The central theme of Batman Begins (2005) is the power of fear, and the struggle to master it. The film depicts a young Bruce Wayne leaving Gotham City, lost and filled with fear and loathing, who returns a man without fear, who takes his own greatest fear and turns it upon those who would harm the vulnerable and innocent. His appearance is also grounded in a reality; gone are the garish chrome of Schumacher’s Batmen, the bold yellow symbol and the fake six pack of Burton’s Batman. Nolan simplifies the suit, making it practical and believable, while keeping iconic traits intact.

The Dark Knight (2008) develops the ideas started in Begins and escalates them, replacing the manipulative, fear exploiting figures of Ra’s Al Ghul and The Scarecrow, with another terrorist in the shape of The Joker. However, while Ra’s and The Scarecrow are driven by the desire to control and dominate, The Joker represents the power of anarchy and madness. He stands the counterpoint to Batman’s quest for order. They are irresistible force and the immovable object. He is the perfect nemesis because, above all else, he proves why there must be a Batman. His actions define Batman’s own, and vice versa. Gotham will forever be torn between these two forces of order and chaos, embodying the battle that dominates the urban landscape in the wake of 9/11.

However, Nolan illustrates that his Batman is not a virtuous figure, casting him in a distinctly grey light. Batman has always had an implicit (0r explicit, depending on the artist) fascist quality to his character. Rather than refuse to address this quality, Nolan makes it a key element of the character’s struggle as the hero of Gotham city. His militarised Bat-suit, aggressive behaviour and, most extreme of all, his secret surveillance network reveal a character willing to cross the line to enforce order, reflecting the encroachment of the power of the state over the individual’s freedom. This is reinforced by Batman’s brutal interrogation of the Joker, which addresses questions of prisoner treatment and police brutality, that unsettle as much as thrill us.

Ultimately, looking at the spectrum of cinematic Batmen illustrates the enduring strength of Batman as cultural symbol. He has become much more than a comic book hero for kids, or simply escapist entertainment. He is modern mythology; through him, his allies, his enemies and his city, we are forced to look at a reflection of our own world. Indeed, the reason why the Dark Knight Trilogy is so effective is because it reflects our current time more ferociously than all previous incarnations, stripping away the excesses and theatricality.

The crucial difference between the previous films and Nolan’s trilogy is that the Gotham Tim Burton and Joel Schumacher portray is a work of fantasy, carved in gothic expressionism and neon lights; a pure spectacle, not a living breathing world. It skips around the reality, where Nolan embraces it. It is in the grime and grit that the truth of the character and the power of his symbolism are fully revealed; cutting through the darkest night, like the bat signal through the Gotham sky.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I watched Batman in the last 1960s, when it was a crime to watch ITV. (I knew that it was based on comics (which may have been franchised off in annuals, though I do not recall any specific Batman comics), but not that they dated back twenty years.)

I don’t think that I knew that there was a film in 1966, but, as Adam West is also in the series (IMDb gives the dates of which as 1966 to 1968), and although I have no notion of how popular the film actually was, I have to think that they were connected – spin-offs almost invariably are: popular film, put on t.v., or vice versa

I confess, as with Star Trek films, to having never seen any of the Batman ones, but, with this interesting piece to ponder, who knows…?